léonie sonning music prize 1986

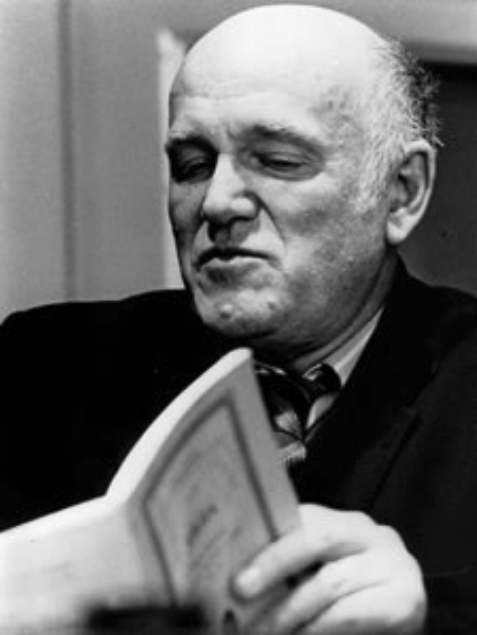

The Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter received the Léonie Sonning Music Prize of 100,000 Danish kroner at a concert on 15 June 1986 at the Tivoli Concert Hall in Copenhagen. The concert was broadcast live by the Danish Broadcasting Corporation’s P2 radio channel.

The prize concert should have taken place on 12 June with a performance of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No 1 conducted by Pierre Boulez, but at short notice both conductor and soloists cancelled. The prize was therefore presented at a solo recital three days later.

The prize was presented by Professor Poul Birkelund, the Léonie Sonning Music Foundation’s chairman. Richter had previously refused to receive the award in front of the audience, but Birkelund managed to give his speech while Richter was on stage. In the prize speech, it was said that ‘in his interpretations, Richter gets as close to the innermost essence of the composer as it is possible for another person to get. Regardless of era, style and character, Richter has managed to bring another dimension to the works in beauty and experience. Tonight we and the Danish music audience are privileged to formalize our gratitude with the Prize.’

citation

‘The Léonie Sonning Music Prize is awarded to Sviatoslav Richter in recognition of his intense artistry at the piano, which uniquely combines expression, characterization and articulation, and is born of a mind and instinct that unfailingly find their way to ideal performances of the chosen works.’

programme

Beethoven Two Rondos, Op 51

Beethoven Piano Sonata No 28

Beethoven Diabelli Variations

Sviatoslav Richter in Denmark

Richter had only performed a handful of times in Denmark. His first performances were in 1961, when he played two solo concerts in Copenhagen, was a soloist in a concert with the Royal Danish Orchestra and also appeared as a soloists with the Horsens City Orchestra conducted by Ib Glindemann.

As a Soviet musician, Richter’s movements were subject to political control throughout his career. Although in the 1980s he was given slightly freer conditions, he was always under the observation of Soviet agents when travelling abroad, even at the prize concert in 1986. The month after the prize concert, on 8 July Richter played another solo recital in Copenhagen, this time in the Odd Fellow Palace, where the program consisted of Schumann’s piano works alongside extra works by Liszt and Wagner. The performance was broadcast live on the Danish Broadcasting Corporation’s P2 radio channel.

The daily press wrote among other things:

With a heavy mind and body, a bear comes lumbering, a little crooked and limping on its big paws. Or maybe a drowned cat? No, not drowned. For Sviatoslav Richter goes to the piano like Garfield does for a dish of lasagna: abruptly and without warning, as if starvation were imminent. Heavy of sound and mind, a Rondo comes rolling along, a little crooked and uneven under the wide hands. Beethoven was no humorist, and is so even less with Richter than others. It blows cold around Olympus as the stone guest makes his entrance. The statue of Beethoven shows its granite jaw in the glow of a reading lamp. The upper register of the Yamaha piano is as sharp and inexorable as steel, while those immense paws, under visible duress, negotiate the lower end.

(Michael Bonnesen, Politiken 17 June 1986)

Overwhelming in the literal sense, Richter can still play with a breathlessly violent attack, reciprocal concentration and a reservoir of sonic and technical resources that few others can match. Perhaps the greatest impact was in the Two Rondos Op 51, which were built from Classical trifles into elaborate, polygonal sculptures with protrusions and ledges.

(Jakob Levinsen, Weekendavisen, 20 June 1986)

Richter plays different roles, and it’s their interaction that proves interesting. He began the C major Rondo all innocent like spring water, switched to a stormy romantic, switched back, became distant like a clairvoyant and then reappeared. He modulated between these characters, as other pianists can only modulate between keys. The sonata became a whole, one long vortex, and the 33 Variations became like a river cruise meandering through constantly new landscapes. The characters can also be rough and tough; Richter is Russian in his playing, too. But they can also be light and bubbly or heavy and tragic. Only the warmly gracious or humorous did not speak in this Beethoven; maybe we meet that side of Richter in other repertoire?

(Thomas Viggo Pedersen, Kristeligt Dagblad 17 June 1986)